Human Monkeypox

Monkeypox is an emerging disease. It was first discovered in 1958 in a captive monkey population, from which it received its name. However, monkeys are not its main reservoir. The largest natural reservoir population is rodents. The full lifecycle and the extent of the reservoir population are still unknown.

Monkeypox is a zoonosis.

The virus:

It is a double-stranded DNA virus.

It belongs to the family poxviridae, genus Orthopoxvirus.

It has two genetic clades – the West African variant and the Central African variant.

The West African clade usually causes milder disease with limited human-to-human transmission compared to the Central African clades.

Distribution:

The virus is endemic in central and west Africa. Most cases have been reported from the DRC Congo and Nigeria. The first human Monkeypox case was found in 1970. However, the number of monkeypox cases has increased significantly in recent decades.

4 cases have been diagnosed in the UK, all related to travel/imported cases. (until 2020)

Image: Monkeypox virus (http://www.uwlax.edu/clinmicro/clinicalmicro.htm University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, Microbiology program)

Clinical presentation:

The incubation period of Monkeypox is 7−14 days (range – 5−21 days)

The incubation period is followed by prodromal syndromes (also called invasion period) -with flu-like illness (fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, cough), asthenia (lack of energy) and lymphadenopathy. Lymphadenopathy, which could be generalised or localised (axilla/neck), is a feature that differentiates monkeypox from smallpox.

After the prodrome, the rash appears (usually after 1-3 days of fever), appearing in any part of the body but most common on the face. It can also affect the mucous membrane of the mouth, cornea and conjunctiva. The rash progresses through four stages—macular, papular, vesicular, and pustular- eventually forming scabs before resolving (taking approximately 2 weeks). Pitted scars may remain after the resolution of the rash.

The patient remains infectious until the scabs are fallen off.

Mortality is approximately 10%. Severe disease is more common, and mortality is higher in children. (WHO)

Complications of Monkeypox:

- secondary infections,

- bronchopneumonia,

- sepsis,

- encephalitis, and

- corneal infection/keratitis leading to loss of vision.

Transmission of virus:

Animal-to-human transmission occurs via – bite, scratch, direct contact with infected material or bushmeat consumption.

Human-to-human transmission – contact with body fluid or infected lesion, aerosol transmission.

Indirect transmission – via material contaminated with body fluid/lesion.

The virus enters the body through broken skin or mucous membranes.

Investigation:

Monkeypox should be clinically differentiated from other rash illnesses like chickenpox. It is difficult, but lymphadenopathy may help to differentiate the disease.

It is an ACDP category 3 pathogen. The laboratory must be notified before sending specimens.

Suspected cases should be discussed with the Imported Fever Service for investigation in RIPL, Porton Down – vesicle fluid/crusts/swab for RT-PCR.

Infection Control and Public Health:

Monkeypox is an ACDP category 3 pathogen.

Immediate notification to Public Health England and Infection prevention control team.

Isolation, negative pressure room preferred. (CDC).

Standard, contact and respiratory precaution.

PPE, including FFP3 mask.

PHE has a guideline for environmental cleaning –

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rare-and-imported-pathogens-laboratory-ripl-user-manual

Treatment:

There is no specific treatment. Management is mainly supportive.

In most cases, the disease is mild, and the patient recovers within 2-4 weeks.

Vaccine:

Smallpox vaccine – Past data from Africa suggests that the smallpox vaccine is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox (CDC) – CDC considers it for outbreak-type situations.

Other treatments with limited data from animal studies or no significant data – Cidofovir, Brincidofovir, Tecovirimat (ST-246), and Vaccinia Immune Globulin. (CDC).

Monkeypox outbreak

Mpox outbreak

Until May 2022, mpox cases diagnosed in the UK had been either imported from countries where mpox is endemic or contacts with documented epidemiological links to imported cases. Between 2018 and 2021, there had been 7 cases of mpox in the UK. Of these, 4 were imported, 2 were cases in household contacts, and one was a case in a healthcare worker involved in the care of an imported case [UKHSA].

In May 2022, an outbreak started mainly affecting gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men without documented travel history to endemic countries. >86000 people are involved in 110 countries. In the UK, approx 3700 cases have been reported until April 2023.

95% of transmission was associated with sex.

98% of the affected population were male.

60% of affected people had HIV. There is no direct relationship with HIV,

94% had mild symptoms, 5-6% needed hospitalisation, <1% died.

The outbreak virus

The outbreak has been caused by mpoxvirus lineage B.1 within clade IIb.

It is not a high-consequence infectious disease (HCID) anymore.

ACDP has now decided that all cases in clade II (including those with non-B.1 lineage associated with travel to West Africa) no longer need to be managed as HCIDs. This is because of the relatively benign clinical phenotype of the currently circulating lineage B.1 within clade IIb, along with firm evidence of the effectiveness of available vaccines, access to rapid diagnostic testing, heightened clinical awareness of this infection, and access to safe therapies with experimental evidence of efficacy. Any cases associated with clade I (previously known as the Central Africa clade) MUST still be managed as HCIDs. There have been no confirmed cases in this clade in the UK. [ref: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/update-on-high-consequence-infectious-disease-hcid-status-of-mpox/]

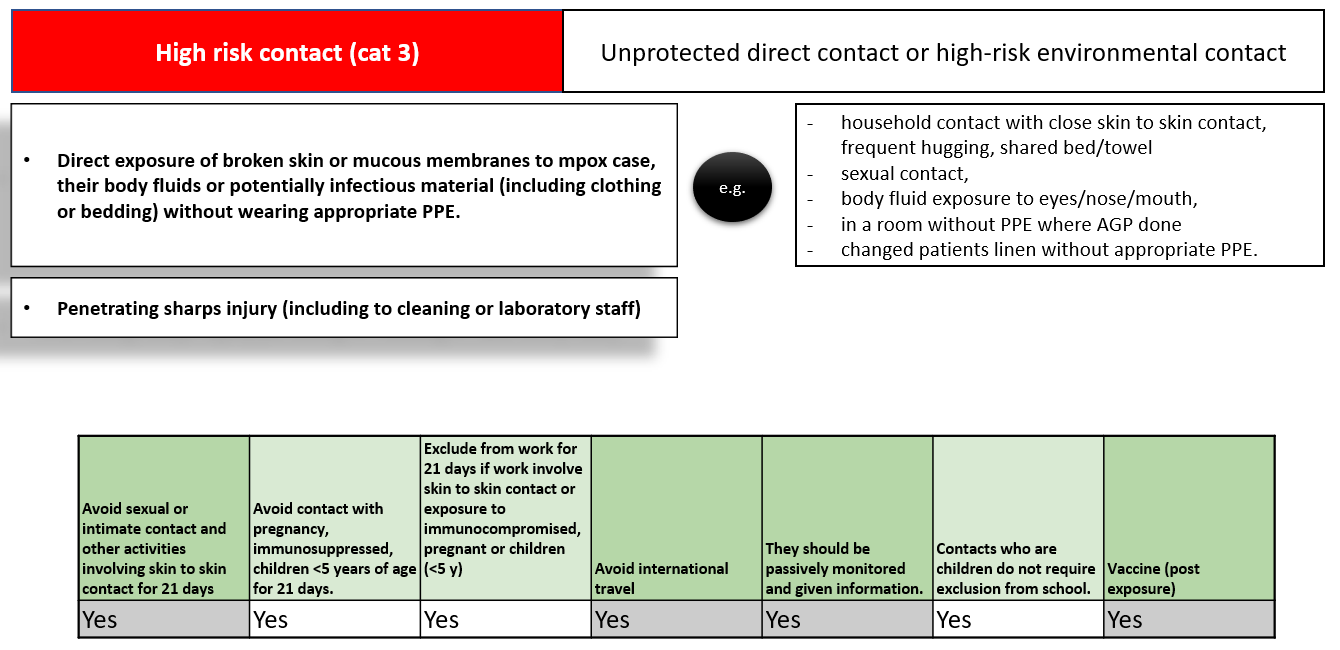

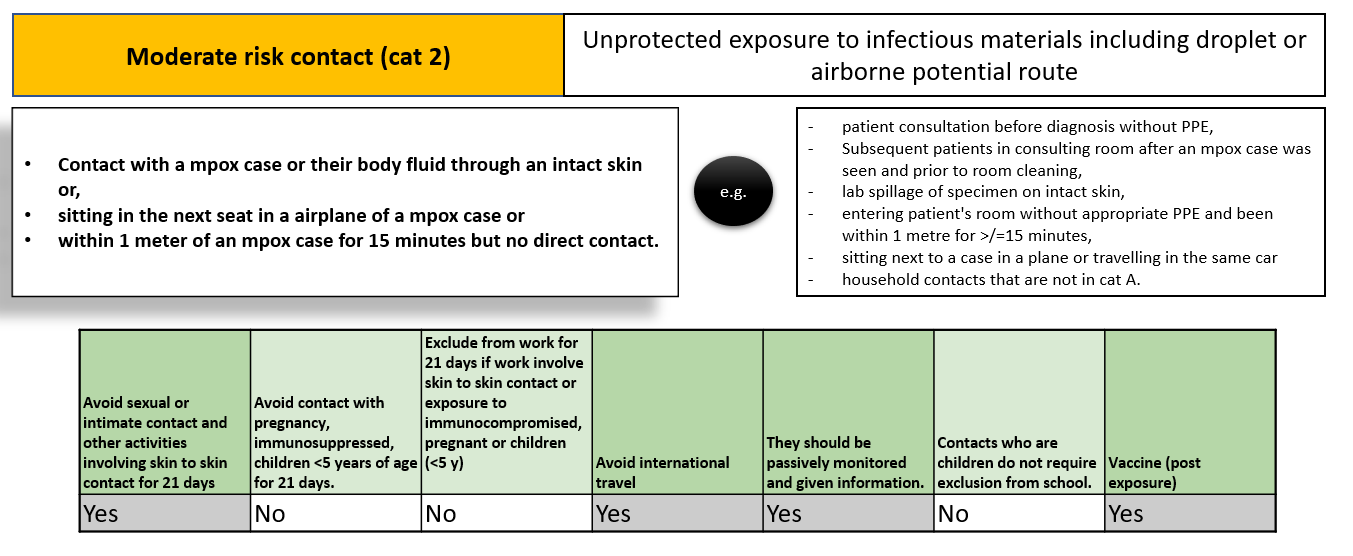

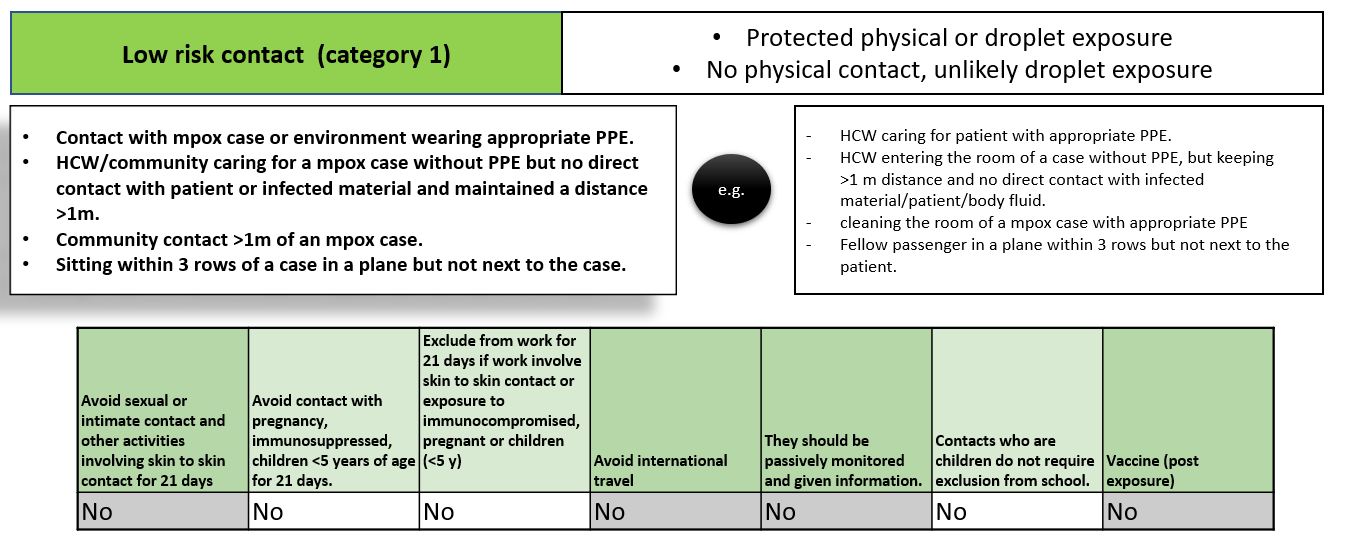

Mpox contact tracing

Mpox vaccine (MVA-BN)

- Third-generation live (replication defective) modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine.

- The virus is attenuated through a serial passage through the chicken embryo fibroblast cells. This leads to very limited replication capability and low neuropathogenicity in humans but retains the immunogenicity.

- Approved for the prevention of mpox and smallpox.

- Intradermal infection for adults aged 18 years and above, at high risk of infection.

It is not licensed for children but likely to be safe (use IM/SC dose - not intradermal), - MVA vaccination induced a detectable response by week 2, with neutralising antibodies peaking at week 6. Over 90% of people seroconvert.

- It provides excellent protection against fatal diseases and may prevent cutaneous disease in almost 80% of people.

- When given post-exposure, rapid vaccination may reduce the severity. However, protection is not as good as pre-exposure as the immunity takes at least 2 weeks to develop.

- There is limited data on how long the antibody post-vaccination persists. The response is better after the booster.

- Adverse effect: local site reactions and influenza-like illness symptoms

- MVA-BN is not contraindicated in pregnancy. However, it has not formally been evaluated in pregnancy. Assess risk vs benefit. It is not contraindicated in breastfeeding.

- HIV/immunosuppression can be used as MVA is replication-incompetent (compared to earlier replication-competent smallpox vaccines).

- Patient with atopy gets more local reactions.

- Dose - 2 doses, given at least 28 days apart.

Booster - a single booster dose at 2 years may be considered for pre-exposure use in individuals who have received 2 doses of MVA-BN and are at ongoing high risk of occupational exposure or for post-exposure use amongst contacts who have had a significant exposure (category 2 or 3)

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- To prevent or attenuate the infection.

- Vaccines be given within 4 days from the date of exposure to prevent the onset of the disease but should be offered up to 14 days postexposure.

- Vaccine given after day 4 may lessen the symptoms but may not protect from the infection.

- Vaccination, up to 14 days of exposure, should be considered in the following groups:

- those at high risk of ongoing exposure, for example, GBMSM,

- some HCWs where the dose will act as their first pre-exposure dose,

- those at risk of more severe disease, such as children under 5 years of age, pregnant women and immunosuppressed

- If someone has had a smallpox vaccine before, give a single dose of MVA.

- If someone had one smallpox and on MVA - no further action

- If someone has one dose of MVA-BN, finish the course; don't restart.

- If someone had 2 doses of MVA-BN in the last 2 years - no further action

- If someone had 2 doses of MVA-BN before 2 years - give a booster.

Who should get the vaccine?

- Community exposure, occupational exposure and laboratory exposure - Category 2 & 3

- Immunocompromised patients should have IM/SC. Intradermal can be used in those with CD4>200.

- Atopic dermatitis patients may have more local reaction-risk assessment.

Vaccine priority

Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM)

- HCW - those providing very close prolonged care or likely to be very frequently exposed to suspected cases during the course of an incident.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

- Children under 5 years of age, pregnant women (especially those in the third trimester) and immunosuppressed individuals.

- GBMSM with multiple sexual partners should be prioritised for the vaccine.

- Those whose last exposure is within 4 days should be prioritised over those exposed 4 to 14 days previously.